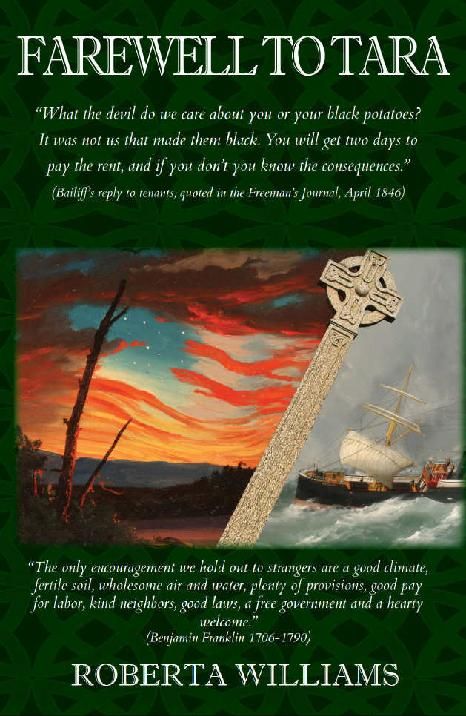

Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings

Description from the Back of the Book

Once Upon a Time...

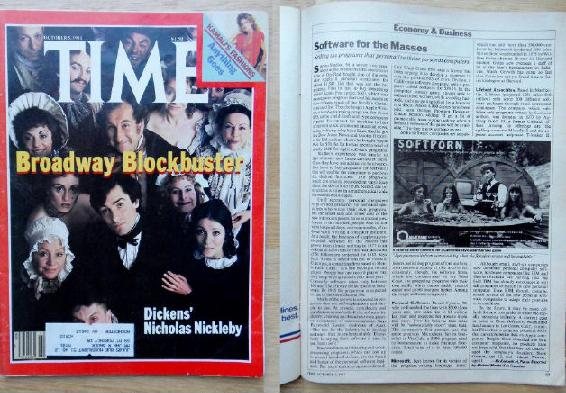

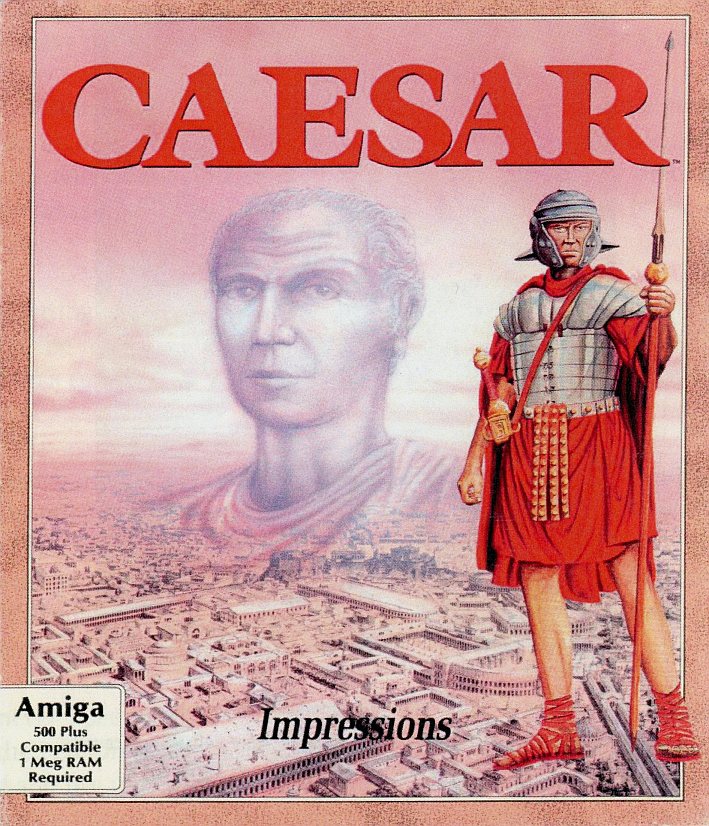

In the time before Amazon, Ebay, or even Google, there was a consumer software company, started by a husband and wife team, that dominated the charts over a nearly twenty-year period.

Sierra On-Line should have lived forever.

This is the untold story of how Sierra was born and how it died. This fairy tale does indeed have a wizard and a princess. But it also has corruption, greed and frightening characters.

UNTIL EVIL INTERCEDED..

Not all evil is hiding in the dark.

Sometimes it lurks where you least expect it.

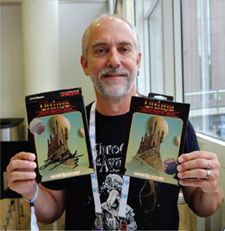

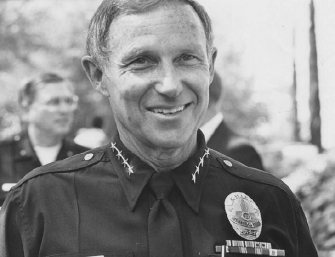

Ken Williams

Founder / CEO Sierra On-Line Inc

NOT ALL FAIRY TALES HAVE HAPPY ENDINGS

The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line

By Ken Williams

Copyright

Copyright © 2020 Ken Williams. All rights reserved.

Published by Ken Williams

ISBN 978-1-71672-736-8

VERSION 2020_09_24 v1

DISCLAIMER: This autobiographical book was written based on the author’s memories. Different people will remember events in different ways. Time has passed and memory has faded. If there are any events which have been recounted inaccurately, it was not intentional. All game related images are the property of the copyright owners and are included herein for historical purposes.

Prologue

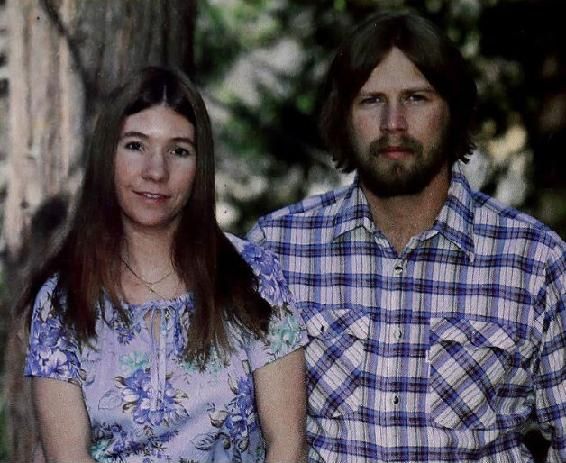

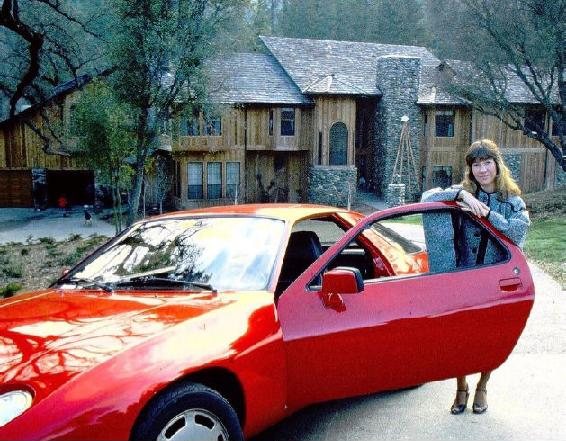

I have three great loves in life: Roberta, computers and boats. That said, this is not a book about any of those things, although the first two of those are important to the story.

My hope in writing this book was that through giving others a front-row look at my journey through life, the mistakes I’ve made and the successes Roberta and I have had, that there might be some piece of it that helps others.

Many of you reading this book may be hoping that this is the ultimate behind-the-scenes tell-all look at Sierra On-Line, the company Roberta and I founded and ran for eighteen years. That’s both true and untrue. This is Sierra’s rise and fall as seen through my eyes. There are no interviews with the game designers. There are very few details about any of the games. There are no game hints. Instead, what you will find are the secrets behind what made Sierra so special. You’ll get a look at the strategies that infused Sierra with a specialness so profound that someone like you might pick up this book and invest time in reading it twenty-five years after Sierra’s untimely demise. You’ll also find that it has a lot of personal background on Roberta and me. As you will see, much of what Sierra was flowed directly from Roberta’s and my personality. You can’t really understand Sierra without a deep dive into how Roberta and I think.

I have thought for years about writing a book about the Sierra experience. My hope was that someone else would write a book and save me the trouble. There has, in fact, been a huge amount written, but I now realize that there are elements of the story that only I can tell. It’s too good a story to leave untold, and there is much to be learned from it. At a minimum, I can guarantee that it is an entertaining story. Whether or not I was able to get it down on paper: Well... you’ll need to be the judge of that.

Ken Williams, July 2020

Chapter 1: (1979) Happy Endings

"We believe that the boat is unsinkable"

- Philip Franklin, Vice-President of White Star Line, builders of the Titanic Cruise Ship

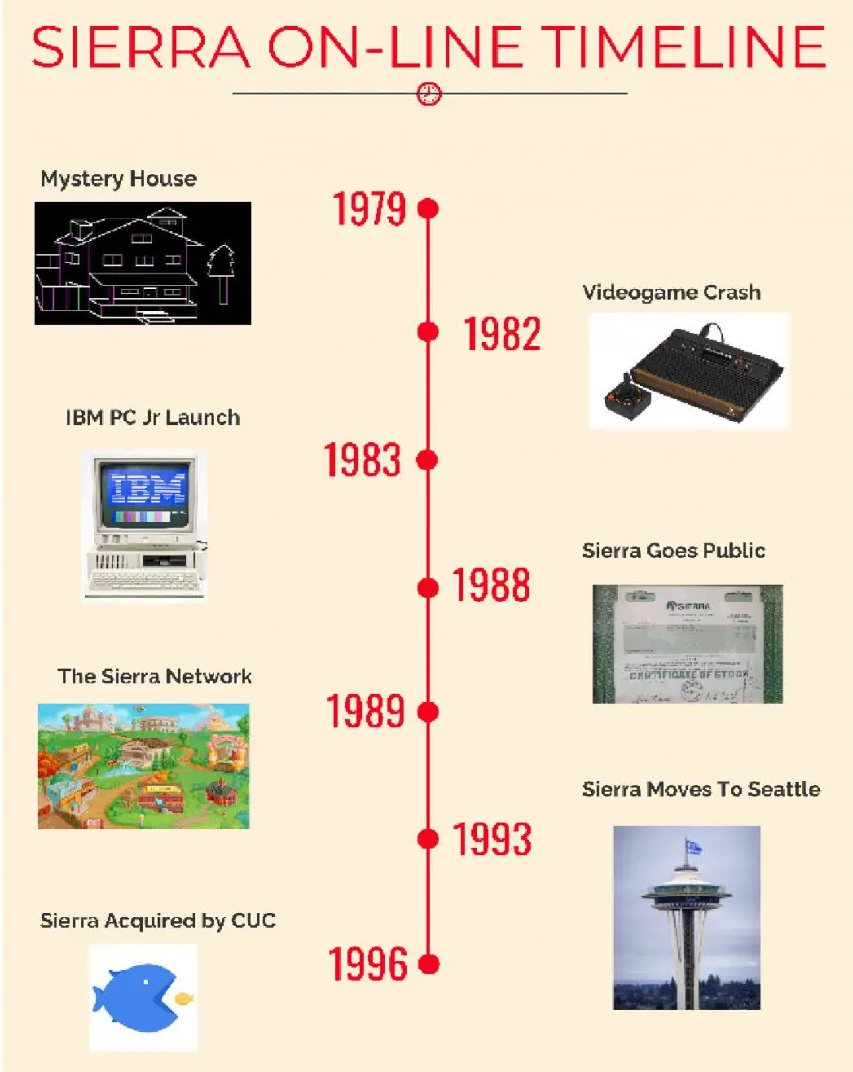

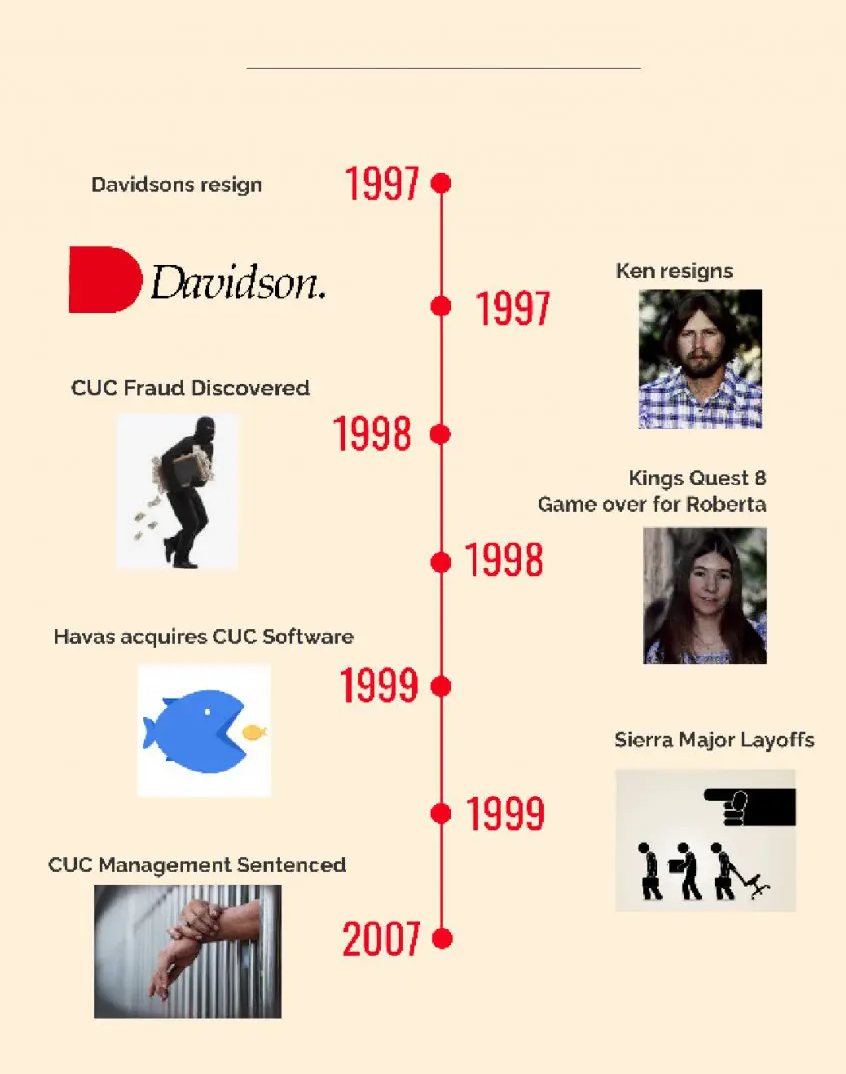

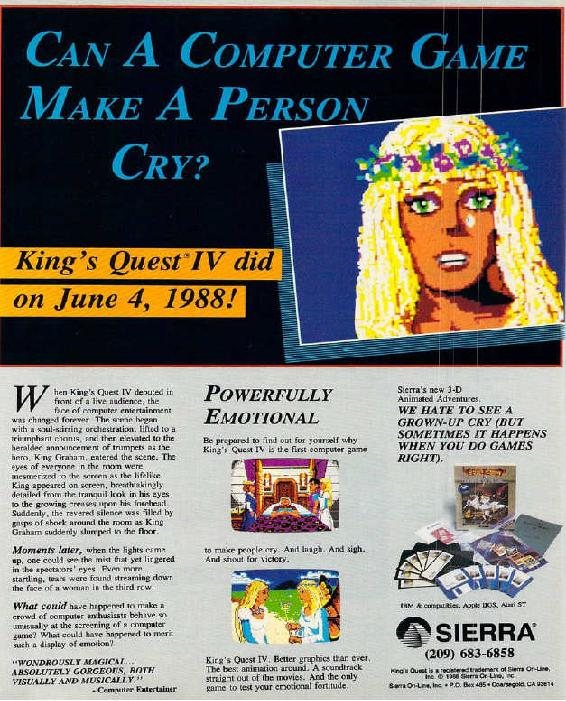

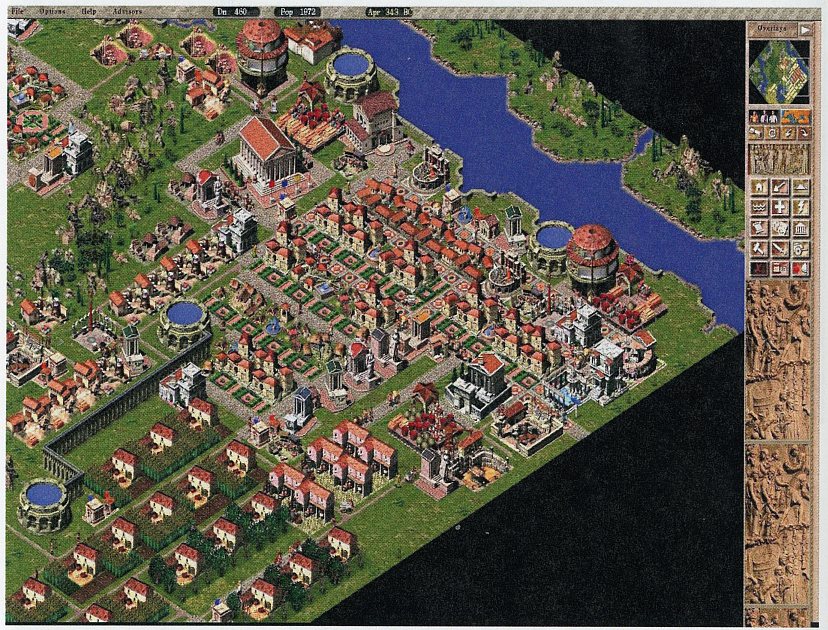

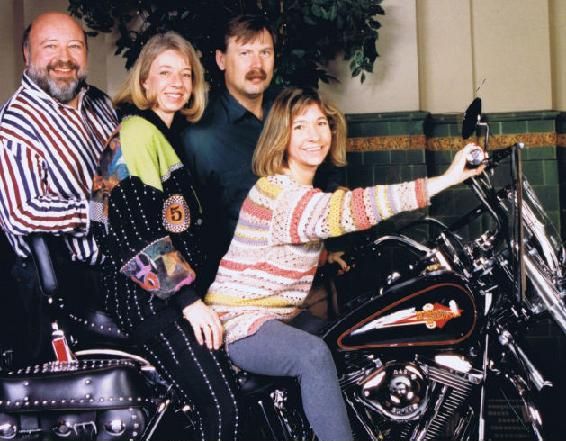

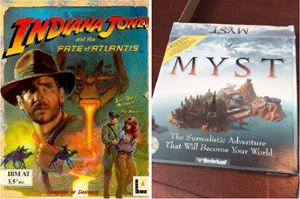

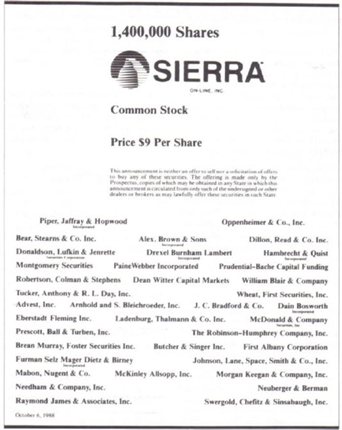

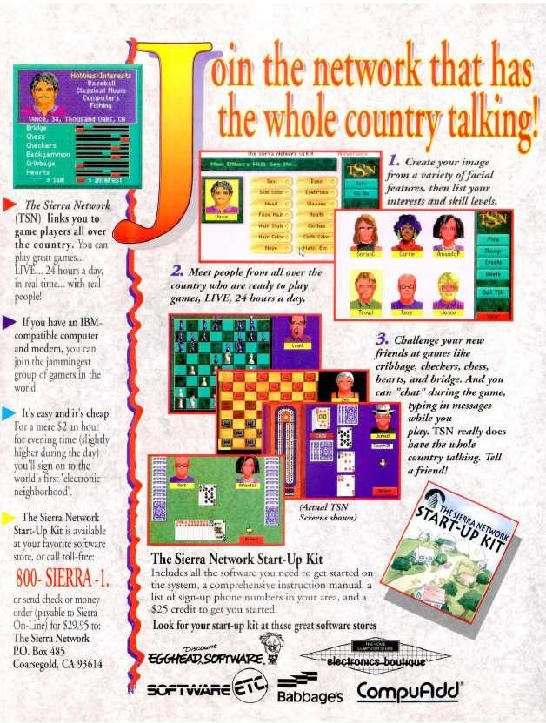

In 1979 my wife, Roberta, designed a computer game that I programmed. That game became the basis of Sierra On-Line, a company we raised from its infancy over a sixteen-year period. By 1996, Sierra was recognized worldwide as a leader in consumer software with one thousand employees producing hit products in education, productivity and entertainment software. From a start on our kitchen table, Roberta and I had built Sierra into a company that would be acquired for nearly one billion dollars.

Sadly, this fairy-tale story does not have a fairy-tale ending.

Instead, the story ends with corruption, lies, litigation, sadness, layoffs, bankruptcies, and prison.

They say that the best place to start a story is...

...at the beginning.

So, here we go (drum roll, please)!

Chapter 2: (1960-1970) Growing Up: TheYounger Years

"If you are born poor, it’s not your mistake. But if you die poor, it’s your mistake."

- Bill Gates

I don’t know the whole story, and don’t care enough to research it, but apparently my heritage is nothing to brag about.

My only memories of my grandfather, on my dad’s side, was of him dying. He was a scrawny little guy with a dark complexion and dark curly hair which didn’t seem to gray. He dragged around an oxygen tank and would sit smoking, drinking whiskey, and spitting into a coffee can.

I’ve been told that he was a colorful character in his prime. He grew up in the hills of Kentucky, sold illegal moonshine and is alleged to have spent time in jail for murder. There is no part of me that wishes we could have spent more time together.

My dad’s older brother was a chip off the old block. He also died of alcoholism.

Somehow, my dad came through what must have been a tough childhood to be a good guy. He was nineteen when he married my mom, who was only sixteen at the time. My mom was young, but this was the back country of Kentucky almost seventy years ago.

My mom’s family was certainly better than my dad’s, but she also came from a broken home.

In the years following marriage my parents had four children, of which I was the oldest. My dad had trouble finding work and loaded the family into a car for a move to California, which at the time was rumored to have plenty of employment and a growing economy.

Dad found work as a TV and appliance repairman for the retailer Sears Roebuck and Co. It wasn’t a great income, but they were able to purchase a small home in a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Pomona CA.

At a very early age I developed an interest in reading. One of my earliest memories was reading the book Moby Dick. Maybe that book started me on the path of being interested in the sea? I don’t know. I was devouring full books at five years of age. It seems impossible, but that is my memory. I read every Superman comic. I read the complete series of books called Hardy Boys; 190 volumes of kids solving crimes. When those ran out I read a similar series called Nancy Drew. I was frequently busted by my mom for reading books, using a flashlight, under the covers late at night. It didn’t slow me down.

We couldn’t afford for me to own the books I was reading. As soon as I was old enough to ride a bike I started hanging out at the Pomona Public Library. I loved that library. Some of my fascination was the access to books, but it was also a place to hide from my home.

My mom and I didn’t get along. I have no recollection of what we fought about, but I know that we did and that I was always happier when away from home. I remember my dad as working all the time, returning only late at night. Looking back on it, I suspect his relationship with my mom wasn’t much better than my own and, like me, he sought refuge elsewhere.

Incredibly, I have very few memories of my childhood. A psychologist might be able to say if I’ve blocked them out somehow. I have no idea, but I don’t really want them back. I have only brief snippets of memory before turning eighteen.

Most of my childhood memories are not of playing. They are of time spent at the library, or at the nearby courthouse. In my early teens I started attending criminal trials. I loved entering courtrooms and sitting quietly in the back watching someone be tried for some offense against society. Murder trials were my favorite. I dreamed of being a lawyer someday. No one ever challenged me but I’m sure everyone wondered what a ten-year-old kid was doing wandering the halls of a courthouse, or why his parents weren’t watching him. I was what you might call a “strange kid.”

I do recall that I was a smart kid. However, this did not translate to good grades. I would quickly read through any textbook and decide I knew everything and then spend class time bored.

It wasn’t just my inattention in class that made me feel out of sync with other kids. I was born in late October and for some reason that allowed me to start Kindergarten at age four. This made me a year younger than most of my peers.

Perhaps it was another manifestation of not wanting to be home, but I was a “joiner” in school. I joined everything; the track team, the chess club, the marching band, the studio band, summer school, etc. It didn’t matter what it was; I wanted to do it.

I supplemented all my at-school activities with a paper route and by selling newspapers door to door in the evenings. I frequently sold more papers than anyone else and won innumerable trips to Disneyland. Somehow, despite my mediocre grades I racked up enough school time that at the end of my junior year, at just sixteen years of age, I was “graduated” from high school.

This was perfectly fine with me. Somewhere along the way I had developed an aggressive personality. All I could think about was getting into college, getting a job, and becoming rich. Note that I said “rich” not “employed” or “successful.” Amongst the few memories I have from that time is the constant thought of wanting to live a different life than the one I grew up in. I read books about business executives who owned yachts and jets, and who hung out with beautiful models in fancy mansions.

I knew that was my future and I couldn’t wait to claim it.

Chapter 3: (1971) Growing Up: Ken Goes to College

"Fat, Drunk, And Stupid Is No Way To Go Through Life, Son."

- Dean Wormer to John Belushi in the film Animal House

No child should enter college at sixteen years of age, but that didn’t stop me. I turned seventeen a month after starting college and that didn’t work much better. Neither my chronological age nor maturity were doing me any favors when I started college.

I was cocky, and it never occurred to me that I might not know everything. Physics was my major, with a minor in over confidence. My goal was to graduate quickly, so I immediately signed up for the advanced level classes.

My aggressive attempt at college was paired with an equally aggressive attempt at earning money. My work as a paperboy had taught me to sell newspaper subscriptions. Each evening I would set out with a group of ten other young men. A van would drop us off on a corner and we’d each go door to door peddling subscriptions. Most doors we would knock on already had a subscription to the paper. But, at least a couple times per block the door would be answered by someone who didn’t really want to have a newspaper delivered to their door. This would start me on my sales pitch.

If you want to win in life, find something to sell, and sell it. Learn to accept and even cherish rejection. Selling is a polite way of describing the humiliation of trying to talk someone into something that they probably don’t need or want and then trying to alter your pitch on the fly as your target plots how to slam the door in your face. Each time the door was slammed I’d learn a little about what I said wrong and what the turnoffs were in my sales pitch. I learned, one slammed door at a time, how to avoid falling into traps that would allow my potential customer to close the door. I had lines to use when they said they were rarely home, for when they said they didn’t like reading the paper, for when they said they were in the middle of cooking dinner. Most doors were closed almost immediately, either because they already took the newspaper or because they had no interest. I had only seconds to size up a person, engage them, charm them, and monetize them.

The newspaper had never seen anyone like me. I was a selling machine. I loved selling, and I especially loved making money. I claimed every sales award and couldn’t stop selling.

I was studying physics at college, but that isn’t how I learned to make a living. It was those nights hustling papers door to door that prepared me for life in the fast lane. In real life I’m incredibly boring and happiest when talking to no one. Most people are surprised when they meet me. Where’s the guy who writes all these books, or makes the games, or is the life of the party? The salesman we’ve heard about? All they see is frumpy old me, and that’s because they are meeting the me I am most of the time. But, give me a product to sell and the switch turns on. And, I do what salespeople do. I sell and I make money.

I mention what I’m like off the playing field because it is relevant. I wasn’t born with sales skills and I’m not naturally charming or persuasive. My ability to sell came through hard work and long hours. I earned my ability one door at a time, and it was an unwillingness to fail that caused me to go to that next door and not give up.

Anyway...

My first year in college was a disaster. It was a wake-up call. I was hustling papers by night and had been promoted to running and training a group of hungry kids who were knocking on doors to sell papers. I had joined a fraternity. I had signed up for courses that I’d thought would be easy but weren’t.

I was seventeen when I joined the college fraternity. I’m sure there are fraternities which are an essential part of obtaining a college education. However, the education I received at the frat house had more to do with alcohol and girls than it did books and studies.\

And, there were even more distractions…

Mike, my boss at the newspaper drove junk cars in a figure 8 race at a local racetrack. During the week he’d patch together a crappy car, and then on Saturday nights he would race the car on a track configured to ensure there would be collisions.

I became Mike’s pit crew, which gave me an interest in repairing cars. Between selling, partying, pit crewing and on rare occasions studying, I was constantly working on whatever car I owned at the time. It’s inconceivable to me now, but I would think nothing of rebuilding a carburetor, swapping a transmission or bleeding brake lines. These days I’m more a software guy than a hardware guy. But not back then. Engine repair came easy to me and I had no fear of taking things apart. I also had a limited supply of common sense and money. My car was constantly under repair and I was constantly broke. Such was the life of my seventeen-year-old self.

Which brings me to Roberta…

Chapter 4: (1971) Growing up: Ken Meets a Girl

"You know that look that women get when they want to have sex? Me neither."

- Steve Martin

I am an impatient person. If I want something, I want it now. When ordering anything on the internet, I automatically seek those things that can be shipped the fastest. This attribute of mine tends to make those around me crazy. This impatience exhibits itself in both good and bad ways. Sometimes very good, and sometimes very bad.

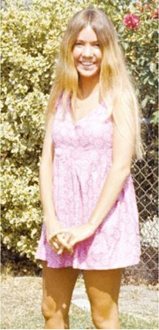

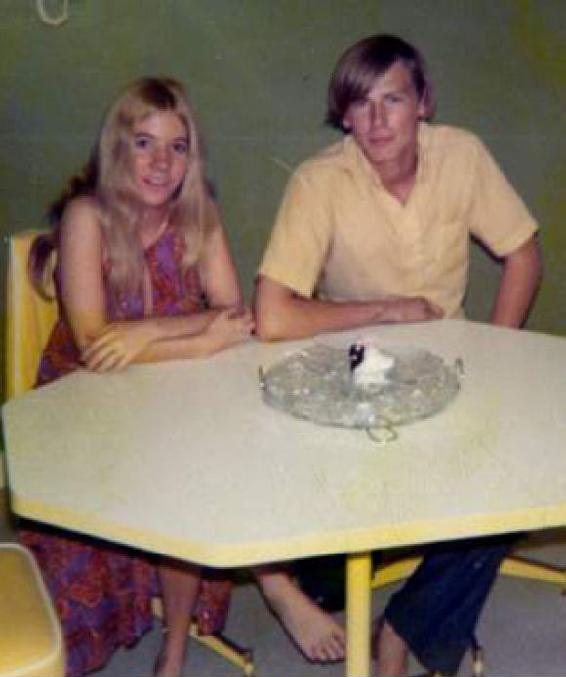

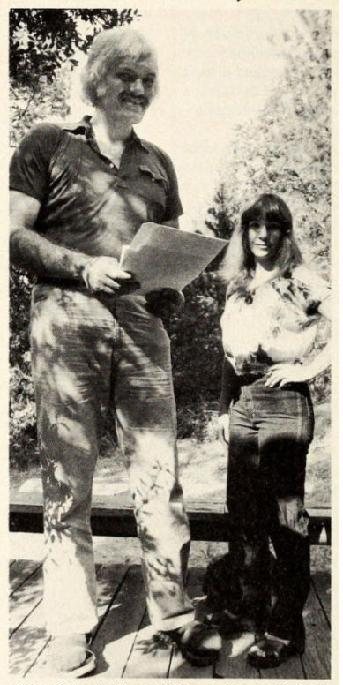

When I met Roberta, she had just graduated from high school. Like me, she was going through the same “having fun phase” that seems to afflict young college students. I was attending Cal Poly Pomona, a four-year university, and she was attending nearby Citrus junior college.

My relationship with Roberta was love at first sight, or to state it more accurately it was lust at first sight. I was seventeen and starting college. She was eighteen and dating a friend of mine while also starting college. We double-dated and I was stuck admiring her from the backseat while my friend drove us to a drive-in theater for a make-out session. I don’t remember much about that double-date other than guzzling an entire beer in one massive gulp, proving I could pee farther than my friend, and that Roberta wore pink underwear. College kids are not always paragons of maturity.

These days, I joke that I am Roberta’s boy toy, because she is a year older than I am, but at the time it wasn’t funny. When we first met, Roberta assumed that I was older than her. I was in college and had a car; all the trappings of someone who had achieved the ripe old age of nineteen or even twenty. However, I was only seventeen. Later, when Roberta found my true age it devastated her and almost broke us up.

When my friend who had been dating Roberta moved on to his next pursuit I asked for Roberta’s phone number. When I called her she had no recollection of our ever having met. It took my best sales skills just to keep her on the phone. Once she remembered who I was, she was unimpressed. She was a hot young Rapunzel, and I was no Prince Charming. I was a tall skinny kid from the south side of town, whereas not only was Roberta beautiful, she lived in the fancy part of town, on a hillside, in a house with a pool!

During our conversation I slowly moved Roberta from saying, “Ken who?” to “I kind of remember you,” to “No. I do not want to meet you,” to “OK. We can meet.” It was one of my tougher sales calls and my foot was bruised from the number of times she tried to slam the door, but ultimately, she agreed to a date.

Roberta at the time was dating guys who were rough around the edges. I was also doing dumb things, but some of my immaturity was layered onto a person who deep down was the perfect definition of a nerd. To try to give the appearance of being cool, I would roll up a pack of cigarettes in my short sleeve shirts. I only tried to smoke a cigarette a couple times, but had convinced myself that this was something that would impress women. Roberta is very good at seeing past outer façades. You can dress a loser up in a suit, or a winner in rags, and two sentences into a conversation she’ll know who is who. This magic ability of hers to size people up within minutes was to become very important later in life and is what really stopped her hanging up the phone when I made that first call.

Roberta’s dad, John, had high aspirations for her. From birth he wanted her to succeed in life. He had decided she should be an optometrist! Neither of us know how John arrived at the conclusion that optometry was the best possible career or her destiny.

Roberta was (and is) petite, and at the time her dresses were even shorter. Her dad was worried about her. She had taken up smoking and was dating guys of dubious character. When I arrived to pick up her for our first date her dad was waiting at the door and, while waiting for her to get ready, he gave me a grilling. I talked about being in college, that I was majoring in Physics and my quest for future success. I shared with him that I was planning to retire by the time I was thirty and expected to become rich and famous.

Did I mention that I know how to sell?

Being a starving seventeen-year-old, our first date was not particularly amazing. We went to a local Mexican restaurant and talked for hours. A couple weeks and a handful of dates later, I informed Roberta that we were to be married. She thought I was insane or joking, but that’s only because she didn’t know me. That was about to change.

Her dad became my strongest ally, and saw in me a chance to rescue his errant daughter. He pushed Roberta from his end, and threw roadblocks in the way of other suitors.

It took a few dates to sell Roberta on the idea of marriage but closing a sale is what I do best.

We had to wait until I turned eighteen to get married. Roberta was working as a ‘typist clerk’ for the County of Los Angeles Welfare Department, in Pomona CA. Her dad, who worked for the County of Los Angeles Agriculture Department helped her get the job. She was making a starvation salary but was living at home, with no bills, and able to save her paycheck each month.

During this time I convinced Roberta to buy a van. I wanted it so that I could transport the kids that I was taking around each evening to sell papers. Understandably, her parents were not excited when they discovered the van had a mattress in the back.

How could life get better? I had a hot fiancée. She had a van. I had a career transporting kids who sold newspapers. On weekends I was fixing and racing cars. I was going to college. I still wasn’t rich, but things were looking up!

Roberta and I were married five days after I turned eighteen. Roberta had achieved the advanced age of nineteen (but, I didn’t hold it against her).

Chapter 5: (1972-1973) Growing Up: Ken Gets an Education

"...I spent three days a week for 10 years educating myself in the public library, and it’s better than college. People should educate themselves- you can get a complete education for no money..."

- Ray Bradbury, author

During my final year of high school our class took a field trip to UCLA (a Los Angeles-based university). The only part of the trip I remember is seeing my first computer.

It’s unimaginable now, because computers are so integral to all of our lives, but computers are a fairly recent phenomenon. At that time, I had never seen a computer. The whole world of modern computer technology was just spinning up. It would be years later, during my first year of college, before I would see my first hand-held calculator.

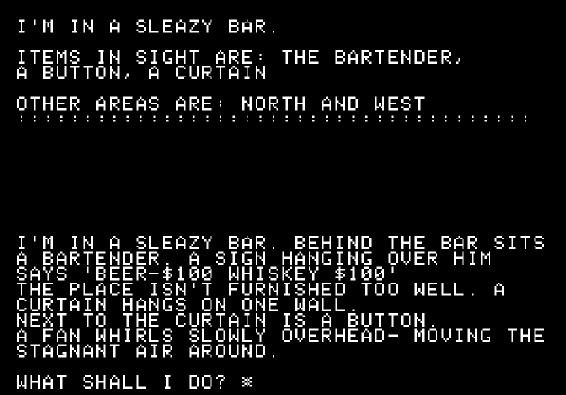

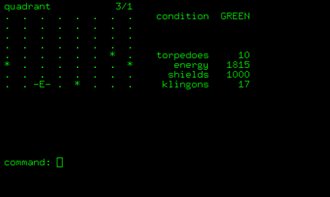

I have no idea if what I saw at UCLA was a computer, or if it was just a keyboard and monitor attached to some far away computer. All I remember is walking up to the keyboard and playing my first computer game. It was a text based game based on the TV show Star Trek.

"Star Trek is a text-based strategy video game based on the Star Trek television series in which the player, controlling the USS Enterprise starship, flies through the galaxy and hunts down Klingon warships within a time limit. The game starts with a short text description of the mission before allowing the player to enter commands. Each game starts with a different number of Klingons, friendly starbases, and stars spread throughout the galaxy. The galaxy is depicted as an 8-by-8 grid of “quadrants.” Each quadrant is further divided into an 8-by-8 grid of “sectors.” The number of stars, Klingons, and starbases in any one quadrant is set at the start of the game, but their exact position changes each time the player enters that quadrant."

- Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Star_Trek_(1971_video_game)

I was fascinated by the experience! I had no idea computers existed or how they worked. I just knew that it was the most exciting thing I had ever seen. I can’t say that it made me want to build software, because I wouldn’t have known the word or the concept. I would have had no idea that computer programming was even a career, and it wasn’t at the time.

There were no computer majors in those days. Physics was selected because when I looked at the course list there seemed to be a lot of computer courses for Physics majors.

My schedule was loaded up with physics classes, calculus classes and computer programming classes.

For the first time in my life I met a challenge I couldn’t handle.

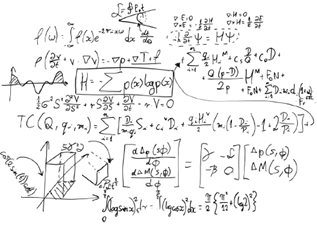

The calculus courses were beyond me. The classes in physics were fun but the advanced calculus courses involved solving differential equations. It isn’t that I didn’t study. I just didn’t "get it."

There was only one college course at which I truly excelled, and that was computer programming.

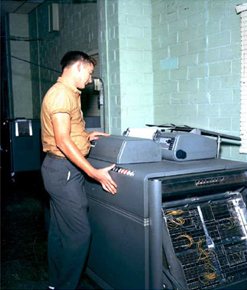

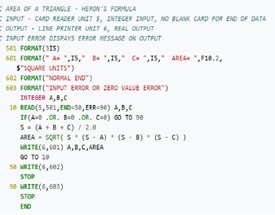

Coding was different in those days. I never saw the computer I was coding on. Instead, there was a room with several keypunch machines, and there was a window where you could place your deck of cards for processing by some unseen computer operator. There was also a basket into which any compiler errors or printout from your computer program, if it ran, would be placed.

To write code I needed to sit down at the keyboard and type out the computer program, one line at a time. Each line that I typed would fill one card.

A computer program consisted of a stack of punched cards; sometimes hundreds of them. Once I wrote a program I’d need to drive to the college, type my program onto a deck of cards, submit my deck of cards to a “card reader” and then come back in a few hours to see if my program ran successfully.

I was working evenings in addition to going to school. Each evening, often many times an evening, Roberta and I would drive out to the college just to see if my program had successfully executed. I would look through the basket of computer printouts, hoping to find one with my name on it. Sometimes Roberta and I would sit for hours waiting for my program to be run, only to see that I had made some small error and would need to replace some card in the deck and submit the deck again, triggering another long wait.

Sound primitive? It was. Coding was a 24 hours-per-day project. In order to debug my program I had to look at the print out I’d get back, hours after feeding my card deck into a card reader. I had various card boxes for various programs. Often, I would submit my program and after waiting four hours and driving back to the school, I’d find that I accidentally mistyped some obscure piece of computer jargon. This would mean making a quick fix and resubmitting the card deck. It also would mean several hours lost. I didn’t mind! This was the most fun I had ever had.

A brief side note: Years later, working as a young software engineer at Bekins Moving and Storage, another programmer brought back my box of cards from the computer room, but no printout. “Where’s my printout? Do I have a bug?,” I asked. He answered, “Yes.” and opened the box. Out crawled a cockroach. Programmer humor is not always funny to non-programmers.

Along with marriage came bills and responsibility. At the time of our marriage, I had completed only one year of college.

Roberta was still working, but to say we struggled financially would be an understatement. When Roberta talks about that job it is with great disgust. This was decades prior to the evolution of the #metoo movement.

“Mr. S[…], who was an oily fat ‘older’ man, probably in his forties or fifties, liked to have me climb up a ladder to file handfuls of folders. The ladder was positioned against a tall wall with shelves of folders all the way up to the ceiling. I was still wearing my ‘short dresses or skirts’ (as were most of the young ladies then!). So he would want me to climb the ladder to ‘file the folders’ in the ‘top shelf’ as he would stand at the bottom of the ladder and look up. He was always making comments of sexual innuendo…”

- Roberta Williams

Within a few months of marriage, Roberta became pregnant with our son DJ. That was the straw that finally broke the camel’s back. It was impossible for me to maintain multiple jobs and go to school full-time. In addition to running a crew that was selling papers door to door, and making pizzas at a local takeout place, I was working weekend nights cleaning up the mess left behind by cars at the local drive-in movie theater. This involved shoveling up dirty diapers, popcorn, and other items too gross to mention.

I had no choice but to quit school and seek a higher-paying full-time job. I quickly found a job sanding fiberglass in a factory. This meant wearing something resembling a space suit to protect myself from the fiberglass powder.

Nothing is duller than working on a factory production line. Not only was I bored, I was hot, sweaty and miserable inside the space suit. To keep myself sane, I started analyzing the processes and quickly came up with ideas to boost productivity. Within weeks, my section of the line was running at nearly double the pace. Instead of this meaning higher productivity it meant my group was stuck waiting for something to do while our output sat on the floor waiting for the next group on the production line to catch up with what we were feeding them. I went to my boss to ask if I could look at optimizing all of the line to reduce bottlenecks.

What my boss saw was a cocky eighteen-year-old kid who thought he knew everything, and who had created complaints from other groups. I explained that I was sure I could double the plant's output. My boss reacted by firing me. He said I was a square peg in a round hole and would be happier elsewhere. He was right. The problem was that we were broke. I was an unemployed college dropout with a pregnant wife. What now?

I had fond memories of my time in college spent learning about computers. It seemed to me like computers might become a real industry someday, and maybe I could find a job where all I did was work with computers. That would be a dream!

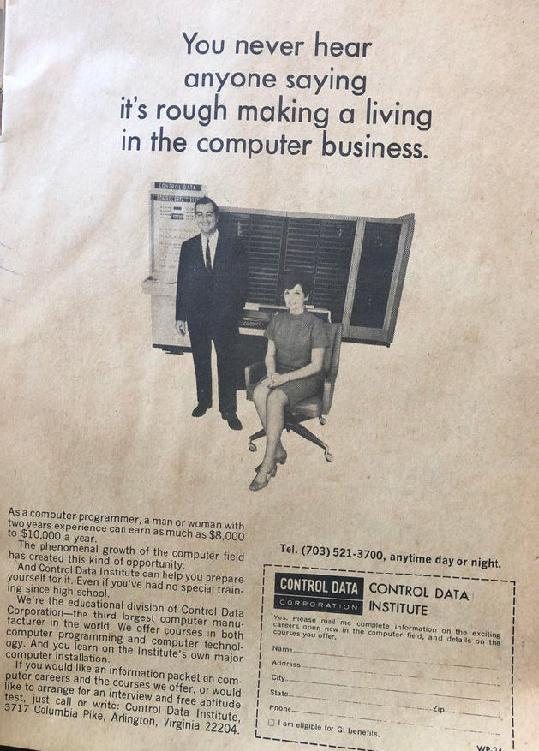

History was changed when I saw an advertisement for a computer programming school which promised BIG MONEY in the computer industry.

The school wasn’t cheap: Five thousand dollars! The good news was that I could qualify for a student loan with a government-backed bank loan and make payments of $47 per month. Payments wouldn’t begin until a year after graduation. They would continue for many years, but if I could get one of those BIG MONEY jobs, it would be fine. The only catch was that I would need someone to co-sign for the loan. They would be on the hook if I didn’t make the payments. My parents weren’t able to co-sign, but Roberta’s parents quickly said, “YES!”

Whereas to complete college I’d have needed another three years of going to school, Control Data Institute (CDI), promised to make me a computer programmer in just nine months.

It was too good to be true.

An excerpt from this ad: "As a computer programmer, a man or woman with two years' experience can earn as much as$8,000 to $10,000 a year"

CDI exceeded all expectations. I have never understood why trade schools aren’t far more accepted than they are. I dreamed of becoming a computer programmer and suddenly, I was in an environment surrounded by others with the same goal, a teacher focused on that goal, and direct access to the hardware needed to attain the goal.

I still had to drive around the kids selling papers at night in order to pay the rent, and supplemented our income by stuffing advertisements into newspapers and delivering papers on weekends. But now, my days were spent learning about and using a computer! Life doesn’t get much better.

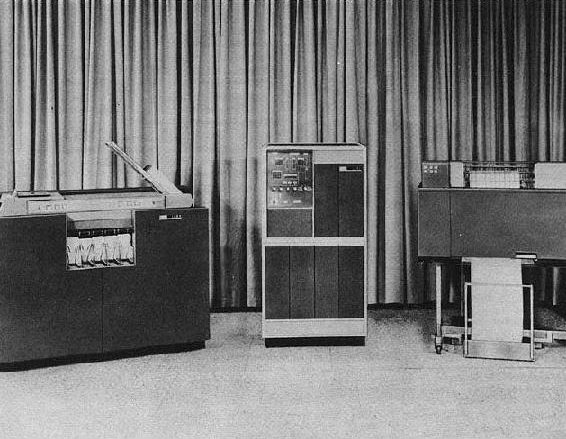

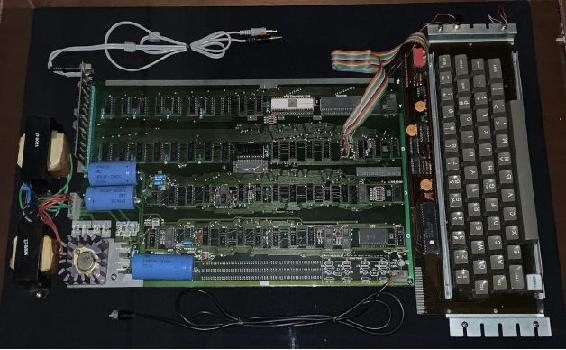

It was a good time to be learning computers because I was able to essentially see the industry being born. The school wanted to take the students through the evolution of computers and after some text book learning about things like binary numbers; we were asked to program one of the earliest computers, the IBM 407 accounting machine. Programming was done by plugging wires into holes on a circuit board!

We graduated from the 407 to a small mainframe computer; the IBM 1401. Programming was now more like what I had been doing in college with programs written using punched cards.

This was my first taste of "real programming" in that we were learning machine language programming. This meant working with the computer at an intimate level. Most computer operating systems and computer languages try to hide the hardware from the programmer. In most cases this is a good thing and allows the programmer to focus on writing their program without worrying too much about the hardware the program will run on. But for real fun, as a computer programmer, you need to get down to the little bits and bytes that are the guts of a computer.

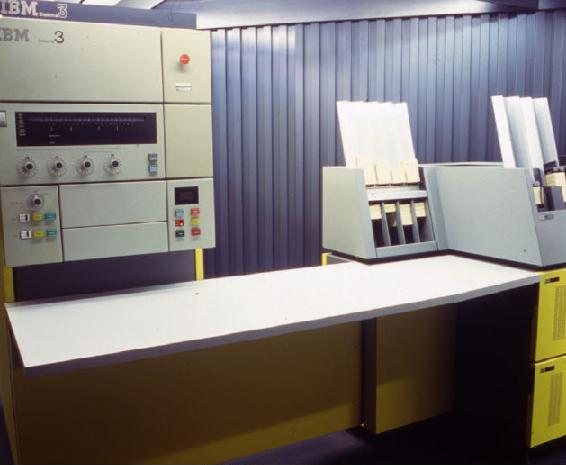

Finally, towards the end of the course, we moved up to a “modern” (in 1973) computer; the IBM System 3. I learned a real computer programming language, RPG II.

School was nine months of pure heaven. I had a knack for computers and quickly separated myself from the rest of the class. I moved at a faster pace than others and would complete class projects in minutes that took other students hours. This gave me virtually unlimited time on the computers to write code.

Unlike college, I was now a hero. I had found something I had a natural talent for and graduated at the top of my class.

It was now time to get serious about finding a job.

Chapter 6: (1973-1979) The Days Before Sierra

"The ladder of success is best climbed by stepping on the rungs of opportunity."

- Ayn Rand, Author

Our son DJ was born in November of 1973, roughly corresponding to the time when I was graduating from Control Data Institute.

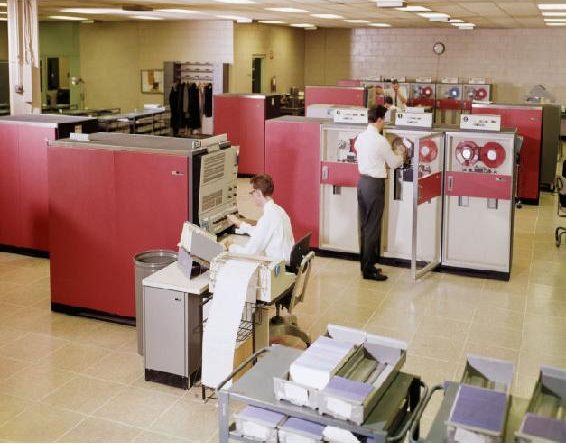

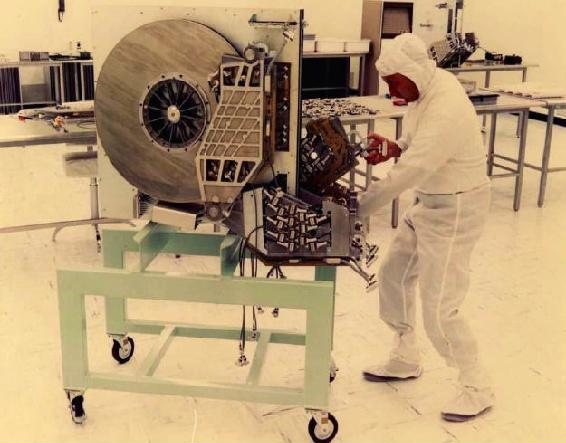

My first job out of trade school was as a computer operator. In those days, computers were giant beasts that filled entire rooms.

These large computers generated enough heat that they had to be cooled by giant, noisy, air conditioning units which circulated air through the room via holes in the floor and ceiling panels. My first job in computers consisted of hanging tapes. Entire databases, such a customer list for a large corporation, were stored on magnetic tape. Sometimes there would be so much data that multiple tapes would be required. My job would be to wait patiently for a light to blink, triggering me into action to load a new tape onto a tape drive. It wasn’t very exciting, but I saw it as the first step into my new career.

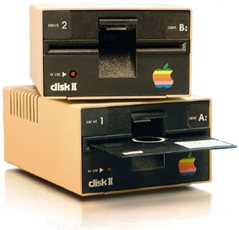

We were living near Los Angeles at the time, and the computer industry was growing rapidly. From the day I started my first job, I sent out résumés seeking a better job. Not only did I want more money, I wanted my shot at being a computer programmer. Within ninety days I was offered a job at a computer manufacturer, Burroughs Corporation. I would have to start as a computer operator, but was promised they would move me into a job programming computers within a year. It was also a chance to work with disk drives instead of tape drives. Burroughs’s disk drives were cutting edge technology. They held an awe-inspiring 250 mb of data on a disk only about four feet in diameter! That is less capacity than even the dumbest of today’s "smart" phones.

That part of my life is a blur. Burroughs gave me my shot at software development within a couple months. As soon as I was able to put the words "computer programmer" onto a résumé, I was back in action looking for my next job.

In those days software jobs were not only easy to find, recruiters would call constantly with promises of a better job and more money. Within weeks of taking each software engineering job, I started looking for my next job. I remember needing to fudge how long I had been at each job, and leave out companies I had worked at, in order to minimize the number of companies for which I worked.

By changing jobs frequently I had learned a wide variety of technologies and programming languages. When seeking a new job I sought two things: More money, and experience that would look good on my résumé.

I confess to having exaggerated my skills on my résumé. If there was a particular skill set I wanted to learn, a technology or programming language, I would claim to be an expert, and if given an interview I would binge study all night prior to the interview and then charm my way into the job.

This is a time in my life when looking back I’d say I crossed over from simple over-confidence into arrogance. This bit me once when I left a well-paying job programming in one language to take another higher-paid job as an assembly language programmer on an IBM mainframe. I studied enough to get the job, but a watchful programming manager quickly discovered I had been fibbing about my experience. I was fired immediately, but had learned enough that I picked up a different job making even more money, coding in IBM assembler, within a couple weeks.

If there is a lesson to be learned from this time, it is that I was always focused on two things: My résumé and my checking account. I wanted a résumé that would give me the flexibility to work for anyone. I studied help-wanted ads seeking the technologies most in demand that paid the most. I knew that if I stayed working for one company, even as a superstar programmer, I’d be locked into 5 to 10% annual pay increases and a promotion every 2 to 5 years. That wasn’t going to get me where I wanted to go.

You, dear reader, should take away from this time in my life that you must always be thinking about how marketable you are. I was right about that. If you have only one skill and the market for that skill is limited, your upside is limited and your downside is wide open. If you get lucky, your company will never have a layoff. If you wait long enough, you’ll get a raise or promotion. If you are good, work hard, and work for the right company, this is a viable strategy. But it’s not one that will give you true job security or allow you to skip steps as you climb the career ladder.

Just a few of the many companies I worked for in the short five-year period before starting Sierra: Bekins Moving and Storage, Burroughs Corporation, Groman’s mortuary, McDonnell Douglas, Fredericks of Hollywood, Sterling Computer Systems, Financial Decision Systems, Informatics, Aratek Services, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, Chaffey Junior College, the State of Illinois, Warner Brothers Studios, Atlantic Records.

Not only was I working a full-time day job, I also started working various contract programming jobs by night and on weekends. Roberta was kept busy with DJ, our older son, and five years later, Chris, our second son.

It was during this time that Roberta and I evolved a system that stuck with us for decades. I would work late into the night Monday through Friday, and even until noon on Saturdays. We would spend the day, on Saturday, and into the evening, dining out or doing something while the kids were at home with a babysitter. This was Ken and Roberta time and no one or no thing could interfere. Then on Sunday, I could work early in the morning, but by the time the kids were up and around, it became their day. We spent the whole day and into the evening focused just on them.

At the ripe old age of twenty, we purchased our first home. And, guess what, as soon as we thought we could sell it at a profit, we sold it and bought another home. And once we had a profit, that home too was put up for sale. We became very good at packing and sometimes would move from a home before we even had time to unpack our boxes.

By 1979, when I first discovered personal computers, I had amassed quite a career, and we were well on our way to financial success.

Chapter 7: (1979) Roberta Has An Excellent Idea

“Destiny is a name often given in retrospect to choices that had dramatic consequences.”

- J. K. Rowling, Author

Roberta’s role in the start of Sierra is legendary. But there is more to the story.

Years before Sierra, while I was busy building my career as a computer programmer, Roberta also worked in computers.

Working was not Roberta’s idea.

I wanted Roberta to work, and she wanted to be at home with our children. The reason I wanted her to work is simple. I felt we could earn more money if Roberta got a job. I also thought she would enjoy working with computers. I loved what I was doing and thought that if she got a taste of it she’d experience the same joy.

The problem was that she had no education in computers, had no experience in computers, and knew little about them. We were living in Springfield, Il. at the time, where I was doing some software development for the State of Illinois.

“It’s true that I knew little about computers, but my exposure had been more than listening to Ken talk about computers. I had spent a lot of time in computer rooms with Ken, not only when he was in college at Cal Poly University but also at Control Data Institute when he attended there, and then at his first computer operator job. Ken would often ask me to change the tape drive and then later the hard disk drives at the various places that he worked. One reason was that he was studying his ‘programming’ and didn’t want to be interrupted by having to change a tape or disk drive. So, I had spent quite a bit of time ‘computer operating’ while Ken and I were ‘waiting’ in the computer rooms. This is how I was able to get a job as a computer operator and do it easily without having to be trained to do it (at Lincoln Land Junior College.) I wasn’t just ‘sitting around playing with babies.’ I was also learning.”

- Roberta Williams (her response after reading what I wrote above)

Roberta did very well as a computer operator, although she had to break in her new boss right from the beginning. On her first day, he asked that she take over responsibility for making coffee for his two programmers and himself. She declined, saying that she didn’t know how to make coffee, which was true -- but also that she didn’t want to learn! A few days later Roberta's boss asked her to type a letter. She immediately said, “I don’t know how to type”, which was a lie, but she didn’t care. She was a computer operator, NOT a secretary!

We lasted under six months in Illinois. I wasn’t making enough money at the time to rent a home with a garage. Instead, we had a carport and each day would start with me hoping the car would start in the freezing weather, shoveling snow out of the driveway and scraping ice off the windshield.

That was our cue to return to the warmth of California.

Roberta’s dad, who has since passed away, worked for Los Angeles County as an Agricultural Inspector. He had a great job with good pay and amazing benefits. John would lecture about the benefits of working for the government.

This gave me an idea. If working for the government was a good thing, perhaps that’s where Roberta should work? The county advertised their jobs, and I was able to see there were many entry level computer positions. However, even though no experience was required, testing was used to see who had the knowledge and aptitude to qualify. In an effort to be fair, interviewing for positions was secondary to test scores.

Roberta is a smart lady. I knew she would do well at any test, but wanted to remove all doubt. So... I devised an idea. I would apply for an entry level computer job and take the test. This would tell me the kinds of questions that were on the test, and I could use that knowledge to help Roberta prepare.

I took the test and, of course, aced it. I could have deliberately given wrong answers, but it was more honest to answer the questions to the best of my ability.

I rationalized my actions by telling myself:

- I was not writing anything down

- I answered the questions honestly

- If the County called and offered me a great job with lots of money, I’d take it

- I would not be giving Roberta answers, I would be telling her what to study

- Roberta would be tested on her knowledge, and she would have that knowledge before she took her turn with the test

Was it cheating? Certainly that could be argued, but form your own opinion. The outcome of my taking the test was that I spent many hours of effort tutoring Roberta in the subject matter that would be tested. Most of the questions were about binary arithmetic, hexadecimal numbers and basic computer terminology. Roberta's a fast learner and a good student. There were two people with the last name Williams who had perfect scores that month.

I received several job offers from the County but was never tempted. Roberta also received multiple offers and began her new life as a computer operator, hanging tapes for the County of Los Angeles.

Her job didn’t last long. Six months? It has been so long that neither of us remembers. Of course, almost immediately after she started working, I wanted her moving up the ladder. Roberta, who had been unenthusiastic about working, was even less so about my idea that she should seek employment as a computer programmer.

Roberta thought I was crazy to insist that she could be hired as a programmer. I talked her into taking a college course in COBOL programming, which happened to be the language I was coding in at the time. I then supplemented her class-learning with personal tutoring and twisting her arm to send out résumés. She grumbled through all of this.

Finding a job for her wasn’t a tough challenge. In the mid-70s, your chances of finding an elephant wandering the streets of Los Angeles were far higher than finding a female computer programmer. I can imagine the look on faces when a résumé crossed their desk from a young aspiring computer programmer named “Roberta.” How could it be? Roberta was snapped up immediately to work as a programmer, coding in COBOL, by Lawry’s Foods of Los Angeles.

Roberta's official title was “COBOL Trainee Programmer.” She was good but had little motivation to really dig in. Also: She was assigned a project working on Lawry’s accounting system, but knew nothing about accounting.

None of this put her job at risk. Who would possibly fire a female computer programmer in the mid-70s? It wouldn’t happen. And, the truth is that she was very good at her job. She would struggle by day with her assignments, then return home where I would tutor her, and fix her code. Her work was always done, and done correctly. My guess is that Lawry’s knew something was unusual about how Roberta was working, but it was a win-win for all.

Roberta's time at Lawry’s didn’t last too long. It was a combination of her not liking programming, our son needing more attention, and my rarely being home.

One constant theme in Roberta's and my discussions was that we wanted out of Los Angeles. There were plenty of reasons; but mostly it boiled down to our saying, “Wouldn’t it be nice to live in the woods?” Our second son, Chris, was born in May of 1979 and our eldest, DJ, would soon be six years old. Did we want him growing up in Los Angeles schools, where we worried about drugs and violence? Plus, the drive time was killing me. I was spending multiple hours a day sitting in Los Angeles traffic.

Unfortunately, as a software developer there weren’t many jobs in small towns. If I wanted to work as a computer programmer, I had to be where I could find work.

We found our solution when I was offered a job at Boeing, the aircraft manufacturer, in Seattle. Today, Seattle is a hub of the computer industry, home to Microsoft, Expedia, Amazon, Zillow and many others. However, none of those companies had yet been born. Boeing was really the only game in town. Seattle wasn’t a small town, but neither was it a big town.

To accept the job offer in Seattle, we would need to sell our home in Burbank, Ca. We listed our home for sale, and it sold quickly, with a 90 day escrow. Boeing agreed to wait for me, but our sale collapsed days from when we thought we’d be moving. We were packed and emotionally we were already in Seattle. It was very disappointing. We wanted out of Los Angeles and Seattle had been our only hope. Boeing withdrew my job offer.

My last full-time job was at a company called Informatics. It was a dream job giving me incredible experience. I was working with the latest technology on the latest systems. It’s tough to imagine now, but at the time IBM dominated the market. There was a saying that everyone knew, “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” IBM’s computers cost the most but were also the best solution, with the best and fastest hardware, the best sales team and the dominant market share. I made it my top priority to study everything IBM related.

Informatics produced a computer language and database system called Mark IV that was very popular on IBM computers. I had always wanted to work on the creation of a programming language or database and saw it as the best job a programmer could have. I was also surrounded by incredible talent. Informatics paid well and hired well. Every day was a learning experience.

However, none of this was as important as the fact that we wanted to move out of Los Angeles. And unfortunately, the only chance of doing so would be to create my own opportunity. I needed to start some company that could be run from home while living in the woods.

Another engineer at Informatics, Bob Leff, and I would have lunch together each day and bounce ideas on companies we could start.

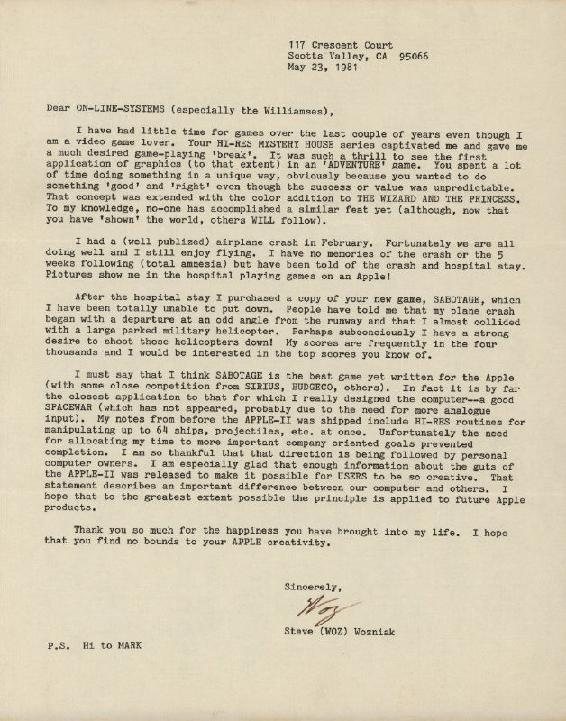

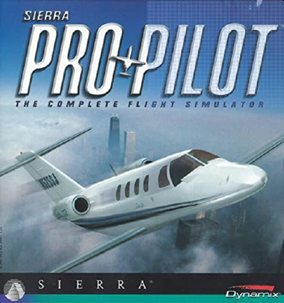

As part of my quest to form some entrepreneurial venture, I noticed that Tandy Corporation (aka Radio Shack) had released a personal computer, at roughly the same time Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were introducing the Apple II.

I saw that a tiny company called Microsoft had put a programming language called “BASIC” onto the TRS 80. It came to me that there might be a market for other programming languages on these personal computers and Bob and I started talking about programming Fortran (another computer language) for the TRS 80.

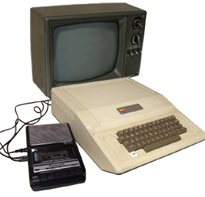

As I was planning my next step, Roberta surprised me with an Apple II computer as my Christmas present. The Apple II was much more powerful than the TRS 80 and could even load programs from standard audio cassettes!

I knew immediately that the Apple II would be our future. It had an incredible amount of memory (16k) and a powerful processor (the 6502).

My friend Bob Leff and I started working to implement Fortran on the Apple II computer. Microsoft was offering the BASIC programming language for the Apple II and I was convinced we could leapfrog them with the much more powerful Fortran programming language.

As I was getting started on the Fortran compiler, I was still working for Informatics as well as several other companies.

My work at one of those companies required that I take home a teletype, allowing me to write code for some unseen remote computer. I think it may have been Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles that provided me the teletype, but that piece of trivia is now lost forever.

I was no stranger to working with devices that were hooked to remote mainframe (large) computers. In fact, my consulting practice, the name under which I did contract programming for many Los Angeles businesses, was: “On-Line Systems.” I had become an expert in working with computers that were accessed via remote terminals. Specifically, I was specializing in technologies called IMS and CICS, and with the IMS-DB system of databases.

There was no such thing as “the internet” in those days. In fact, there was nothing even remotely similar to the internet. There were remote terminals connected to mainframe computers, but they were wired directly to the computers. Not all terminals were clunky like the teletype I brought home. Most of the terminals I was working with had CRT (Cathode Ray Tube) screens and used a system to display pages of data which was not unlike the modern system that the internet uses to display web pages today (HTML).

To use the teletype, I had to load a program from paper tape, then use an acoustic modem to connect to a remote computer. The modem was a little gadget that would transmit data as sound. The sounds were a little like morse code in that seemingly random beeps and boops would represent data being sent as audible sound over a phone line.

This modem was a “110 baud modem,” which is the technical way of saying “incomprehensibly slow." "How slow?." you might ask. Well... Most pictures I take with my iPhone are around 2 megabytes. To transmit 2 megabytes of data at 110 baud would take at least forty-five hours, if the connection would last long enough to ever complete. Suffice it to say that no one was sending pictures via an acoustic modem.

It is possible that I just brought home the teletype to play with. At least, that’s the only purpose I can remember the teletype serving. I somehow was able to dial into MIT via the teletype and play games.

There weren’t a lot of games to play, and I couldn’t find the original Star Trek game that originated my interest in computers.

What I did find was a game called "Colossal Cave Adventure."

Curious what it was I ran the program and to my surprise I was greeted by these words...

Huh? Now what? What was I supposed to do? There didn’t seem to be any instructions.

All I could think of was to type: “HELP”

Interesting! I experimented, typing various sentences that didn’t seem to get me anywhere, until I typed the simple phrase “GO BUILDING.”

This was getting very interesting. Roberta was nearby in the kitchen, so I called her over to the computer. She read over my shoulder and then pushed me aside. She wanted to try. I was not happy! I had just gotten rolling and she took away my toy.

I was not able to get anywhere near the teletype for the rest of the evening. Roberta was ignoring the world around her. She stayed that way for hours. I recall her staying up all night to finish the game, but her recollection is that the effort spanned several weeks to a month.

My Fortran compiler was moving along and had been made much easier by Apple introducing a floppy disk drive. Audio cassettes were slow and unreliable whereas the floppy disks held approximately 110,000 bytes (characters) of information. They were still miserably slow, but at least they were more reliable.

Meanwhile, Roberta was sad that she had completed the Colossal Cave and wanted something similar to play.

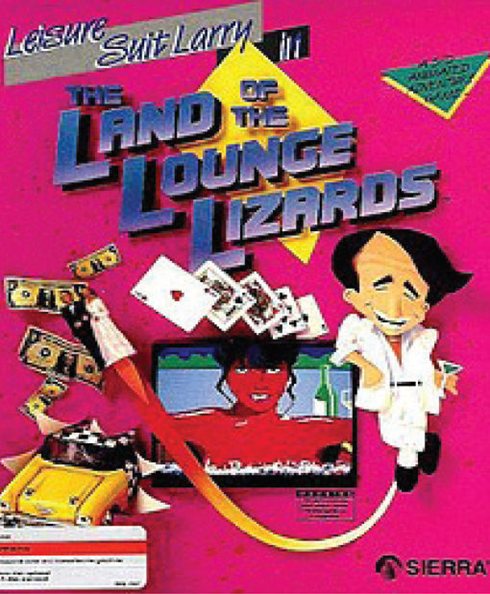

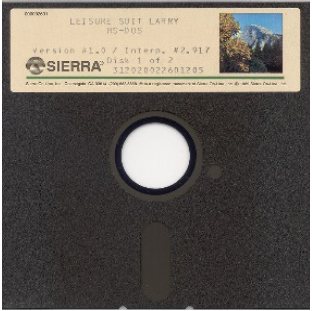

I ordered her some games on audio cassette from a Florida company called "Adventure International." They were created by Scott Adams and followed the same basic style of play as the Colossal Cave. The player would use type written commands to explore a world that was described via text. Roberta raced through the games, and then started thinking about if she could build a game of her own...

She tried to show me what she was working on a few times but I was busy and never really focused on it. I was keeping busy working on my compiler in addition to working both a full-time and several part-time jobs.

And then, one Saturday night, our lives took a dramatic turn when Roberta said she wanted to take me to dinner and had a surprise for me. I had no idea what the surprise could be. We made reservations at a fancy steakhouse (The Plank House) and arranged a babysitter.

Whatever it was she wanted, it seemed to be important to Roberta.

At dinner, Roberta laid out her idea for an Adventure Game of her own. Roberta was envisioning a game, to be called Mystery House, which would be loosely derived from a combination of Agatha Christie’s novel, "And Then There Were None" and the board game "Clue." In Mystery House there would be eight people, locked in a house, and murdered one by one. As Roberta was describing the killings, I was trying to hide under the table. Roberta was using words that are not typical during a romantic dinner, like: “kill,” “murder,” “gun,” “knife,” “blood,” and “strangle.” The couple at the table next to us was overhearing pieces of the conversation and could see Roberta across the table animatedly and loudly saying things like, “Wouldn’t it be great if I could give him an icepick in the eye?”

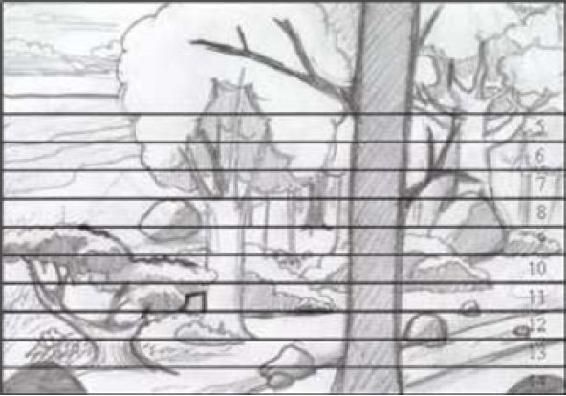

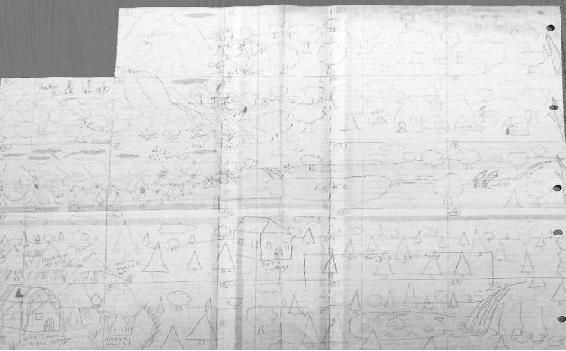

Roberta continued the discussion when we returned home, spreading across our kitchen table a large piece of paper filled with hand-drawn bubbles and connecting lines. The bubbles were labeled with descriptions like “The Porch,” “The Graveyard” and “Attic.”

As Roberta was talking I was listening closely. She had finally captured my interest! I started thinking about how such a game could be programmed. It seemed like it might be a trivial programming effort and something I could whip out in an afternoon that might make Roberta happy. This was obviously something she was passionate about.

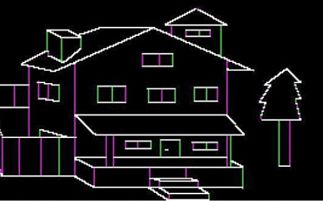

Thinking out loud, I asked Roberta, "I wonder if it would be possible to have pictures of some of the places in the game?" Roberta asked if it would be possible and I said, “I don’t think so, but it would be fun to try.” If I was going to sidetrack from my compiler for a few days it should be for something fun, and I had already started wondering if pictures were possible on the Apple II.

As soon as I had suggested graphics, I started backpedaling. It might be fun to experiment, but was almost certainly impossible. Pictures are data intensive. It would take a stack of floppies to display just one picture.

Roberta was excited! She had no doubt I could figure something out, and she wanted me to immediately quit screwing around with the Fortran compiler and build her a game.

Roberta was a woman on a mission. And, when Roberta wants something, the only thing to do is to get out of her way.

Chapter 8: (1980) Roberta Gives Birth (And, It’s a Game AND a Company!)

"I’m tough, ambitious and I know exactly what I want. If that makes me a bitch, Okay."

– Madonna, Recording Artist

Roberta was not going to rest until I figured out how to build her a game. The actual game itself seemed easy to code. But, she had thirty or forty little bubbles on her diagram, each representing a different game location. It would be impossible to portray even one of those locations graphically on an Apple II computer. I believed Roberta was wasting her time, but I also couldn’t stop thinking about how it could be done.

Roberta was so confident that I’d figure it out that she started sketching the locations. Watching her draw, I had an idea.

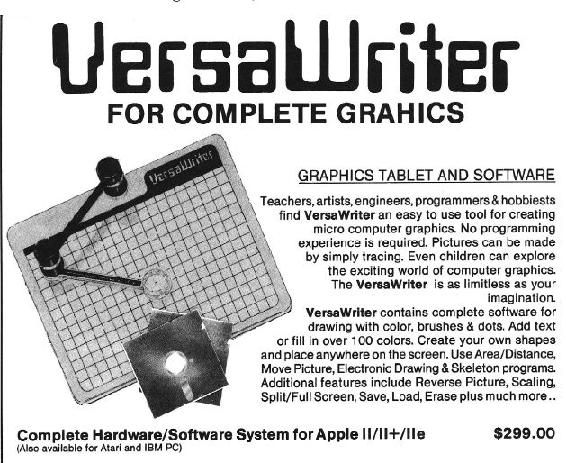

While visiting one of the very few computer stores in California I saw something called a "VersaWriter." It was being used to trace pictures into computers.

My "big idea" was to use the VersaWriter to mark end points of lines into the computer rather than storing the picture pixel by pixel. To understand what I was thinking, imagine a simple rectangle placed on a grid. It could be represented by a series of numbers; for example 10,20,30,40. This could mean something like: Start 10 pixels (dots) from the left and 20 pixels from the top, and draw a rectangle that has its lower right corner at 30 pixels from the left and 40 pixels down. A line could be drawn the same way using the same four bytes (numbers). This seems brain-dead obvious today, but was unheard of at that time. By using this approach, a line, or a rectangle, or even a circle, could be described in a tiny amount of data.

The VersaWriter came with software, but I’d need to write my own software which would allow Roberta to "trace" her hand drawings into the computer one point at a time. The local computer store connected me with the creator of the VersaWriter who thought it was a cool idea and he supplied me with the technical information I needed to write the utility Roberta needed.

Roberta taped her hand-drawn picture to the tablet of the VersaWriter. Using the arms of the tablet, she started marking end points of lines. As she hit the end of each line she would press ENTER on the Apple II keyboard. Within minutes the picture was on the screen! The opening picture of the house took only about 150 bytes to display! More detailed pictures might take a few more bytes, but suddenly her game was looking possible. Even if pictures expanded to 200 bytes, seventy pictures would only consume about 14,000 bytes, or 1/5th of a floppy disk!

I had to advise Roberta not to put too much detail into her pictures. The 80,000 bytes possible on a floppy isn’t much storage. Somehow that tiny amount of disk storage was going to need to hold both the pictures and the game program.

I was still thinking about my Fortran compiler, and Roberta's game was interfering. Not good. I knew that I needed to somehow get Roberta what she needed to build her game or I’d never get any work done on the compiler.

She needed a utility that would let her build the game without bugging me, and that would compile the game to be small enough to fit on a floppy. To understand the problem, grab a loaf of bread and try to squeeze it to fit into a shot glass. It’s possible if you squeeze hard enough, but it may never taste the same again.

There were multiple problems that needed to be solved simultaneously:

- I would need to write a utility for Roberta to produce the art.

- Her art would need to be stored (digitized) to fit in a tiny space.

- Roberta would need one or more utilities that would allow her to script the game.

- She would need some compiler that would assemble the pieces of her game and somehow fit them onto a disk, and into the limited memory of the Apple II computer.

No problem!

Ultimately, I came up with a very simplistic table-driven approach to the game which was based on a series of simple text files. I forget exactly what I did, but my recollection is that the files were Rooms, Objects, Messages, Verbs, Nouns and Actions.

My top priority, when writing the code that drove the game, was multi-tasking (in the human sense). I wanted Roberta to be able to develop the game while I sorted out the technology. To accomplish this, I split the game logic from the actual code that would produce the game.

Roberta wound up “coding” the game on a series of plain old paper pages. These were then typed into simple text files, which were then encoded to take up the least possible space on the floppy disk.

She described each location in the game as follows:

| ROOM # | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 1 | You are in the front yard of a large abandoned Victorian house. Stone steps lead up to a wide porch. |

| 2 | You are in an entry hall. Doorways go East, West and South. A stairway goes up. |

Objects would have been described using the same approach:

| OBJECT # | NAME | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | KNIFE | A sharp and pointy knife |

| 2 | CANDLESTICK | A beautiful silver candlestick |

Verbs:

| VERB # | SYNONYMS |

|---|---|

| 1 | GET, GRAB, TAKE |

| 2 | PUT, DROP |

Nouns:

| NOUN # | SYNONYMS |

|---|---|

| 1 | DOOR, OPENING, DOORKNOB |

| 2 | HOUSE, HOME, BUILDING |

| 3 | KNIFE, KNIVE |

| 4 | CANDLESTICK, CANDLE STICK, CANDLE |

Messages:

| MESSAGE # | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 1 | You can’t |

| 2 | If you did that you would die |

| 3 | You pick it up |

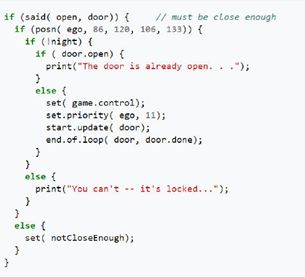

Where it got a bit more interesting was on Actions. I needed to give Roberta a way to write code. Roberta did have some programming experience, but had limited programming skills. I would be writing the real code (an “interpreter”) in assembly language. My interpreter would read her series of tables and decide what to put on screen.

The Actions table was where the action would happen. To describe it in a table, Roberta needed to indicate the room the action would take place in, what conditions needed to be met for an action to occur, and what would happen if the action were met.

| ACTION # | INPUT | CONDITIONS | ROOM | ACTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HAS Knife | HAS OBJ KNIFE | 1 | DROP OBJ KNIFE GOTO ROOM 2 EXIT |

| 2 | HAS Knife | 1 | DISPLAY MSG 1 |

It has been forty years and I have long forgotten exactly what the code looked like, but I do remember that Roberta quickly caught on and was able to produce the action table without my involvement.

While Roberta was busy filling reams of paper with her game design, I was busy coding a series of utilities:

- She needed some simple data entry screen that would allow her to type in her design and create the text files that I’d be compiling.

- She needed a compiler that would take her text files and compile them to a series of numbers.

- She needed a run-time interpreter that would display the game according to her compiled design.

To put all this into perspective, you need to remember that there were no tools at the time. All of the animation and source editing/debugging tools that exist today weren’t available then. I somehow was able to code in machine language (aka assembler), but I don’t remember how I did it. Perhaps Apple itself had some utilities, but they weren’t available to me. My guess is that whatever I did, it was very primitive and miserably slow and painful. And, don’t forget, I was working a full-time job, plus several part-time jobs at the time. Squeezing out hours to work on Roberta’s project was not easy.

That said, I do believe I was displaying Roberta’s pictures within a week or two, and that within a month I had built enough of the data entry tools, compiler, and interpreter that she could start debugging her game.

I had been making regular visits to the local computer store where we purchased my Apple II to see what new peripherals or software might be available. At the time there weren’t many computer stores to be found, probably no more than two or three in the entire Los Angeles area. During visits I would talk about my upcoming Fortran compiler and how it was going to revolutionize software development for the Apple II.

On one such visit I showed off an early copy of Roberta’s game. It was a showstopper. Everyone in the store gathered around the computer and watched. They all wanted to type. I didn’t want them anywhere near the computer because I knew how fragile the game was. Type the wrong thing and the game would crash. Unfortunately, I couldn’t hold people back. Everyone wanted to try typing into the game.

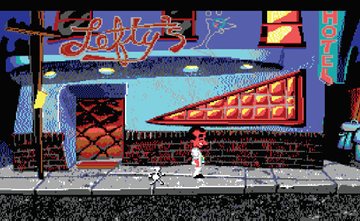

The store owners, Vivienne and Gene, asked when they could buy copies to sell in their store. I was shocked and couldn’t wait to get home and tell Roberta. Her little project, that I considered a distraction, seemed like it might actually be something!

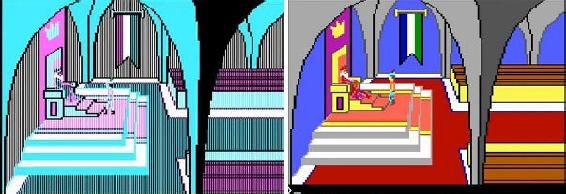

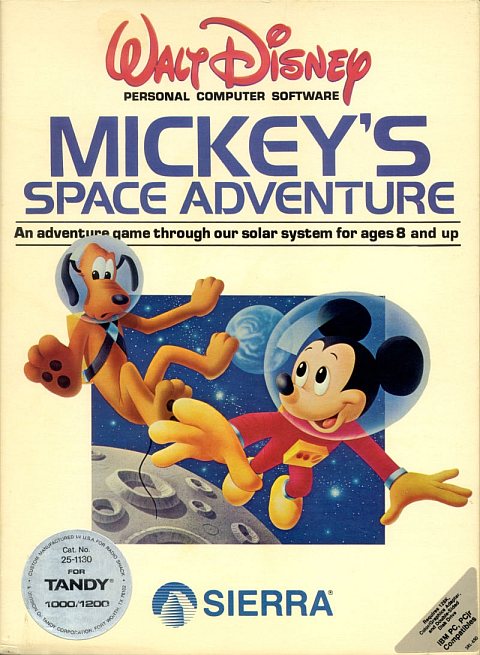

What seemed like a long game development cycle wasn’t long at all. Roberta bought the Apple II computer for Christmas of 1979. Mystery House was released in May of 1980.

Roberta designed the packaging for Mystery House (which was nothing more than one printed page stuffed into a Ziploc bag along with a floppy disk.

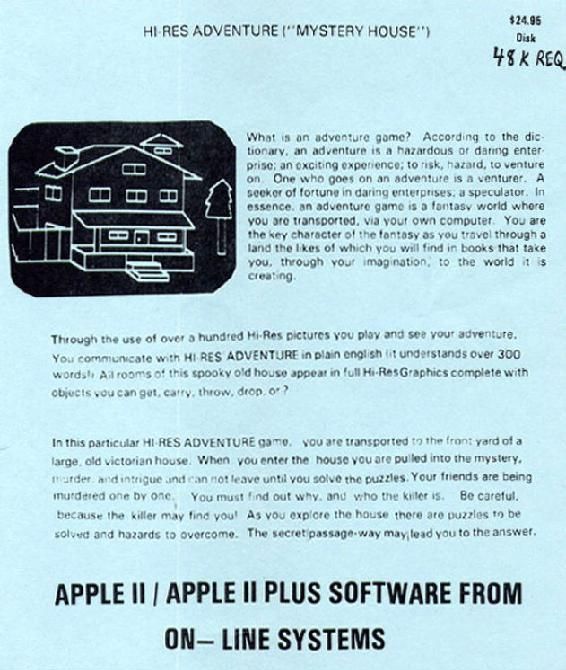

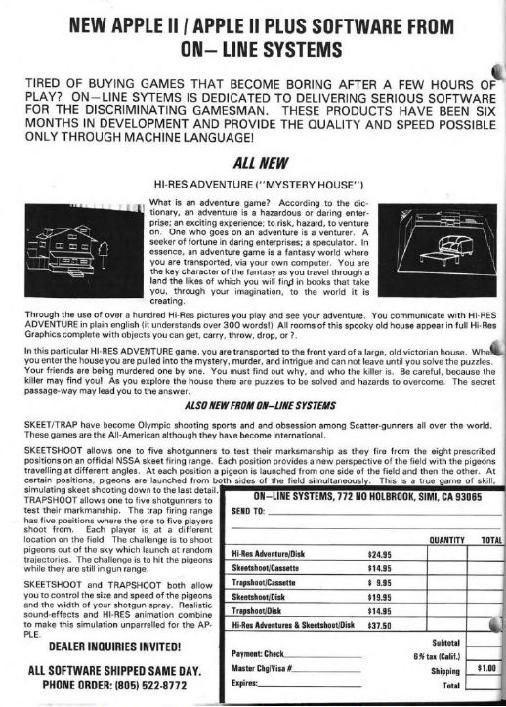

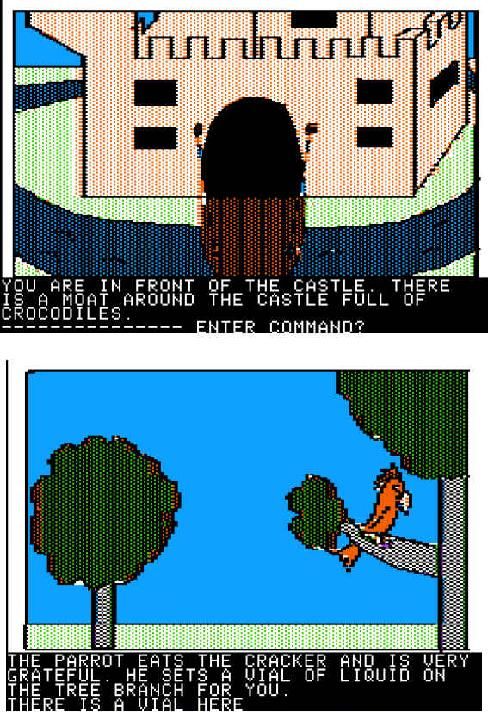

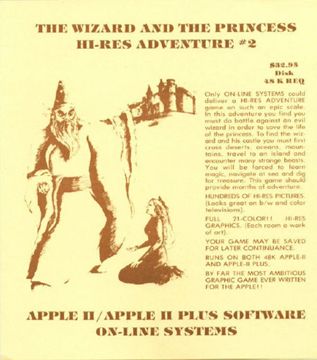

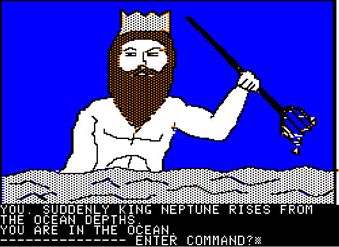

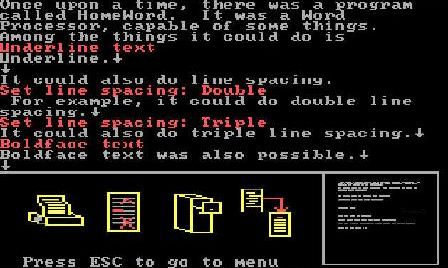

"What is an adventure game? According to the dictionary, an adventure is a hazardous or daring enterprise; to risk, hazard, to venture on. One who goes on an adventure is a venturer. A seeker of fortune in daring enterprises, a speculator. In essence, an adventure game is a fantasy world where you are transported, via your own computer. You are the key character of the fantasy as you travel through a land the likes of which you will find in books that take you, through your imagination, to the world it is creating.

Through the use of over a hundred hi-res pictures, you play and see your adventure. You communicate with HI-RES ADVENTURE in plain English (it understands over 300 words!) All rooms of this spooky old house appear in full hi-res graphics complete with object you can get, carry, throw, drop or ? ..."

- From the Mystery House packaging

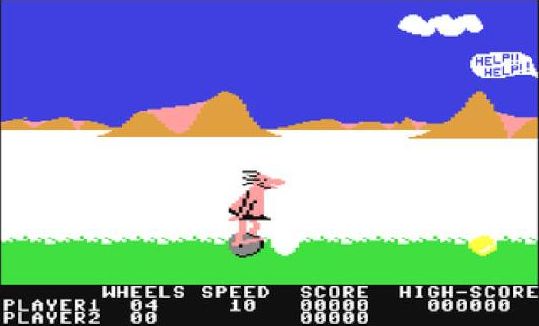

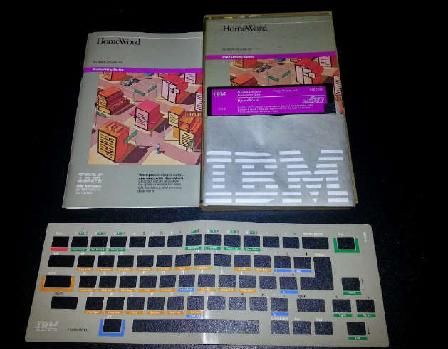

There was no such thing as desktop publishing software in those days. We had to produce the "packaging" by going to the computer store to use their printer, and then hand taping the words onto a piece of paper, and then Xerox the pages for the packaging one at a time. The game consumed more memory than intended and some early purchasers could not get it to run. As you can see in this picture, after retailers identified the problem, I updated our packaging by handwriting the memory requirement onto the package: Retailers didn’t complain. They happily sold a lot of memory upgrades for Apple II computers.

Roberta’s game was an instant hit!!!!!

- INTERLUDE -

(A brief pause in the story, so I can wedge something in)

Chapter 9: Let's Talk About Letters

"Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work."

- Thomas Edison

NOTE: As you read this book, you will see chapters that are labeled "Interlude," like this one. In some cases these chapters are extraneous to the story. For example, there is an interlude where I provide some tips for software developers. There are also interludes that are critical to understanding Sierra, but span the entire Sierra experience, and couldn’t be pinned down in time, such as where I talk about Sierra’s marketing and product strategies. Some advance readers of the book suggested I move these to the back of the book, but I like it better with them sprinkled throughout the book. Do not fear; enjoy the sidetracking, just keep reading and the story will continue.

Before I talk more about Sierra I want to digress and talk about how I have always graded myself and those around me. Feel free to skip this chapter, but those of you puzzling over how I think will find some insight here.

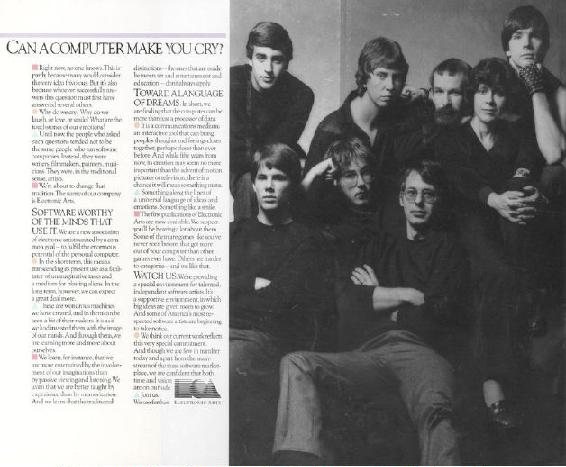

You may have heard the expression, “She’s (or, He’s) an A player.” It’s a form of ranking people within an organization.

There aren’t a lot of A players.

"A players attract A players. B players attract C players"

- Steve Jobs

Ranking is not a popular notion. In today’s world there is a push against grades. Schools are trending towards passing everyone. IQ tests, SAT tests, College Entrance exams, etc. are under assault. I will not speculate on if that is right or wrong. Form your own opinion on what you think the world should look like and how it should run.

What I can tell you is how I mentally class people and why I think it is important. And, regardless of what they may say, even those people who fight the hardest against grading systems hope to find an A player when it comes time to get their refrigerator repaired.

I will start by defining the categories starting at the bottom.

F players do everything to avoid working. They find reasons why they can’t work. If they do work they tend to show up late, count sick days and then exaggerate the slightest pain in order to go on disability.

D players are marginally better. They work, but only to the extent needed to get a paycheck. D players are perfect for factory jobs. They will usually show up on time. They will put in their time. And, they will go home.

C players are good solid workers. They are well prepared for their jobs and can be counted on.

B players are the standouts around the company. They do their jobs better than those around them. If the business hits the skids and two-thirds of everyone has to be laid off, B players, and above, are the ones you keep. If you call a B player at night or on a weekend, they will happily respond and show up at the office if needed.

A players are true heroes. Give them a project and it will be completed ahead of schedule. A players don’t make excuses. They accept blame when they make mistakes and they never play "point the finger" games. They will take a project you thought would take a month and complete it ahead of schedule with higher quality than expected. They not only "know their stuff" they have a sense of the bigger picture and have potential well beyond the job they are doing. A players don’t usually need to be called at night or on weekends because they are the ones doing the calling. A players know about problems before they occur. Waking them up is always ok because, if there is work to be done, they probably aren’t sleeping anyhow.

Triple-A Players. Your chances of hiring one of these is slim. They have a broad knowledge base and don’t really have a life outside work. You don’t need to call them at home on nights and weekends because they are already at work. And, if something goes wrong, they don’t need to call anyone. They just fix the problem. Or, more often, they plan way ahead so that problems don’t occur. Even one of these in an organization will kick things into gear.

My personal goal has always been to be a Triple-A player. I can’t honestly say that I have ever achieved that goal. If I’m awake I’m usually either working or thinking about working. If I’m reading it is usually some sort of self-help book.

This topic is critical if your goal in life is to climb the ladder of economic success. I’m not saying that D and F players never get promoted. In fact, if you’ve ever dealt with really large companies or government bureaucracies, you will find plenty of them. I do not mean to imply that Ds and Fs are bad people. They are often family oriented, perfect parents, highly intelligent, and charming. But in their lives, climbing the ladder is far less important than coaching their kid’s soccer team. Speaking from a management perspective: If my goal is to run a business efficiently, and to thrash the competition, I’m not going to get there with D and F players.

If you want to win big in life, decide early that you want to be a Triple-A player. Recognize you may not be, but get as close as you can, and then do one more thing: Surround yourself with B or better players. Be hardworking and smart. Surround yourself with smart hardworking people. In fact, if you are a B player or above, you will not succeed in an organization full of C and lower players. Cs only hire and promote Ds or Fs, whereas B and above seeks the elusive Triple-A player. If you are an A player working for a C player, you can expect to be fired or demoted. Count on it and don’t be surprised. Complain about your boss, or work harder than those around you, and you will not last long.

If you think the above system is unfair, don’t agonize over it, and don’t try to change it. The system is what it is, and doesn’t care what you think. If you are an A player, you are going to climb the ladder quickly if you are in the right company. If you are an A player and seem stuck in your position, change jobs. Don’t wait long or stay and whine. Just move to a new company. When you resign, if your employer recognizes you as an A player they will pay you more to stay, or offer you that long sought-after promotion. And, if they don’t, you are making the right decision to leave.

The main thing is to not lock yourself in. Always think about your résumé and how it appears, and make sure you have the kind of experience that allows you to move freely from company to company. Part of being an A player is to be “in demand” by the right kinds of employers. If your résumé only qualifies you for one particular position in one particular city, you are doomed to mediocrity or less. That’s fine if your career is subordinate to your personal life. And, don’t get me wrong. Being an A player is not for everyone. There are many people, probably most people, who could be an A player if they thought it was important to do so. But... is money all there is to life? All I can say is that, if your goal is to "win the game" financially, you need to take it seriously.

Chapter 10: (1980) A Brief Flirtation with Software Distribution

"If a window of opportunity appears, don’t pull down the shade."

- Tom Peters

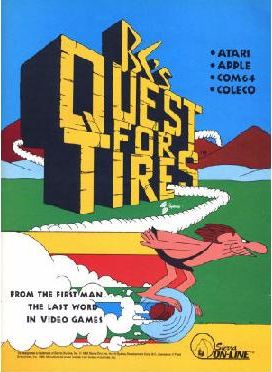

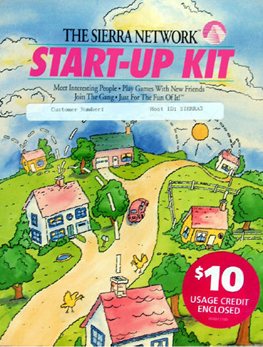

Roberta and I were amazed by Mystery House’s success. I took a few dozen copies to the local computer store and they sold out immediately.

In 1979, there weren’t many computer stores in the country. I called them and they immediately asked for copies. Word spread quickly about the game and suddenly computer stores were calling me begging for copies.

In this ad, which ran while the company name was still On-Line Systems, Mystery House was promoted as a Hi-Res Adventure, indicating that Roberta and I already had more adventure games in mind. The address shown was our home, and the phone number was our home phone. No cell phones in those days!

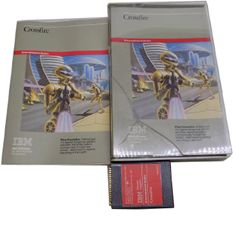

I was suddenly speaking with every computer store in the nation and saw this as an opportunity to make money. I called Scott Adams, who had made the Adventure games that Roberta played, and asked if I could help sell his products. My new idea was to not only sell Roberta’s game, but to become a distributer for other software companies. There weren’t many companies selling Apple software, and I called them all.

Within days I had become the West Coast Distributer for several software companies. They sent me copies of their software via UPS and then I delivered them to retail stores up and down the West Coast.

My younger brother, John, who was still in high school, was tapped to help with distribution. Here is a brief description he wrote of his time peddling Sierra products in Chicago:

"...It was May of 1980 and I was living in a small bedroom community an hours’ train ride from Chicago. I received a box via UPS from my big brother in California.

I had no idea what was inside and when I opened the box, things didn’t get much clearer.

The box was filled with close to 100 Ziplock plastic bags with a piece of light cardboard and a square piece of plastic inside. The cardboard inserts were printed in black on blue or brown with simple graphic images and a few lines of text. In the upper corner of each was a price- $19.95 to $24.95.

I talked to my mom and realized that Ken had been trying to call me for a few days. (I had just graduated from high school and hadn’t been home much. I had a 3rd shift at a payroll company and an active social life.) I gave him a call and discovered that what he had sent me were computer games.

His proposition was simple. "Go to the local computer stores and show them what you have. I’ll give you 25% of everything you can sell."

I had played computer games before at Ken and Roberta’s house. They had a Radio Shack TRS-80 and games for the computer were loaded from cassette tapes. Ken explained those little square wafer things were like cassettes but faster and that the computer store would understand what they were.

I was perhaps just too young to be intimidated by the idea of trying to sell something I had never used, couldn’t explain and didn’t understand. They say blessed are fools and children, and I had a foot in both camps, I guess. (This was to be a common theme in the early days of the rise of Sierra- Ken gave a chance to a lot of people like myself who had absolutely no reason to deserve one. We often had success just because we were too naïve to understand what we were up against.)

I checked the phone book and discovered seven "computer stores" in the greater Chicagoland area. Three were downtown- a place my dad had said I wasn’t allowed to drive to or he’d stop paying my car insurance- but I found an address for one in a suburb up north that sounded like it was findable. I loaded up my '72 Pinto with that box of games, and I was on my way the next day. No appointment or anything. I just went.

It was a weekend, and when I got to the store mid-day it was packed with customers who seemed in no hurry to buy, but were eager to talk to each other and the clerks about technical things using words I had never heard and did not understand. I finally found a clerk who would talk to me long enough to hear my story about the mysterious items that my brother had sent me. He was as curious as I was about what these disks contained, but customers came first, and it was another hour or so before he had a chance to unpackage a “diskette” and “boot” it into the computer.

When the first screen of Mystery House appeared on the primitive green screen computer monitor, the constant din of the computer enthusiasts who had been crowding the store dropped just a bit. The screen was small, but the crowd quickly surrounded it as best they could.

The clerk seemed to understand immediately what the game was about and started trying to figure out the text commands. Soon enough the crowd behind them was shouting suggestions and seemed enthralled as the story moved from scene to scene.